We must state historic facts and nothing less.

— Deputy Grand Chief Gordon Peters, Turtle Clan, Eelünaapéewi Lahkéewiit (Delaware Nation)

The Pavonia Massacre

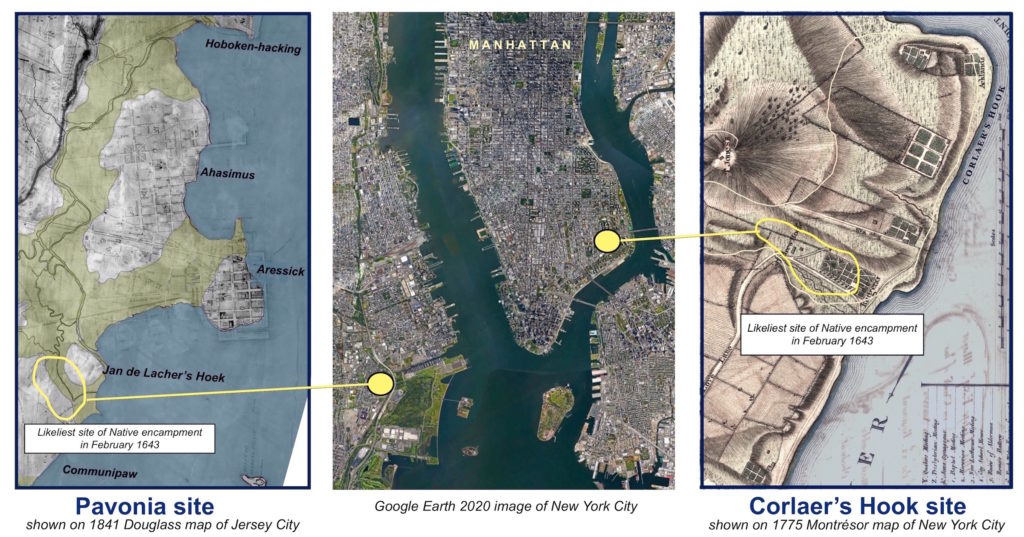

On February 25th, 1643, Dutch soldiers, under cover of night, attacked an encampment of Lunaape/Lunaapeew/Lenape peoples — specifically the Tappan, Hackensack, and Wickquasgeck communities — on the west side of the Mahicannituck (or Hudson River) at Pavonia, now known as the Communipaw neighborhood of Jersey City, New Jersey. At the same time, armed Dutch citizens attacked others encamped at Corlear’s Hook, in the current-day Lower East Side, New York City. At least 80 people were killed at Pavonia, and 40 at Corlear’s Hook. This event, known as the Pavonia Massacre, was one of the first major acts of violence by the Dutch in the Americas, and would result in an almost three-year conflict between the colonizers and Indigenous peoples of the estuarial region, thus further accelerating the dispossession of vast swaths of Indigenous land. Learn more here →

In collaboration with For Freedoms, Josué Rivas (Mexica and Otomi) of INDÍGENA, Hôtvlkucē Harjo (Mvskôkē-Creek), The Public History Project and our Lunaape/Lunaapeew/Lenape community partners created a billboard campaign near the original site of the 1643 Pavonia Massacre. The billboard remains on view from February 24 – March 14, 2022 to resurface this under-acknowledged massacre that continues to impact our present.

Why did THE PAVONIA MASSACRE happen?

In 1638, Willem Kieft became the new Governor of New Amsterdam, taking over from Wouter Van Twiller, who had forged friendlier relationships with the Lunaapeew/Lenape/Lunaape people of the estuarial region. Kieft was corrupt and ineffective by many accounts, as was his secretary Cornelis Van Tienhoven. Kieft wanted Indigenous peoples of the region to pay tribute to him, in the form of wampum, maize, and animal skins, for “protection” from Northern groups that the Dutch themselves had armed. When his wishes were not taken seriously, he began planning to wage war. A council of twelve Dutch citizens disagreed with Kieft. However, on February 22, 1643, Van Tienhoven produced a petition signed by only three members of the 12-man council; two of whom had close ties to him. This petition gave Kieft the political cover to mount an armed attack on the two encampments. Please see the Historical Context section below for further details and background.

Introduction and Geographic Context

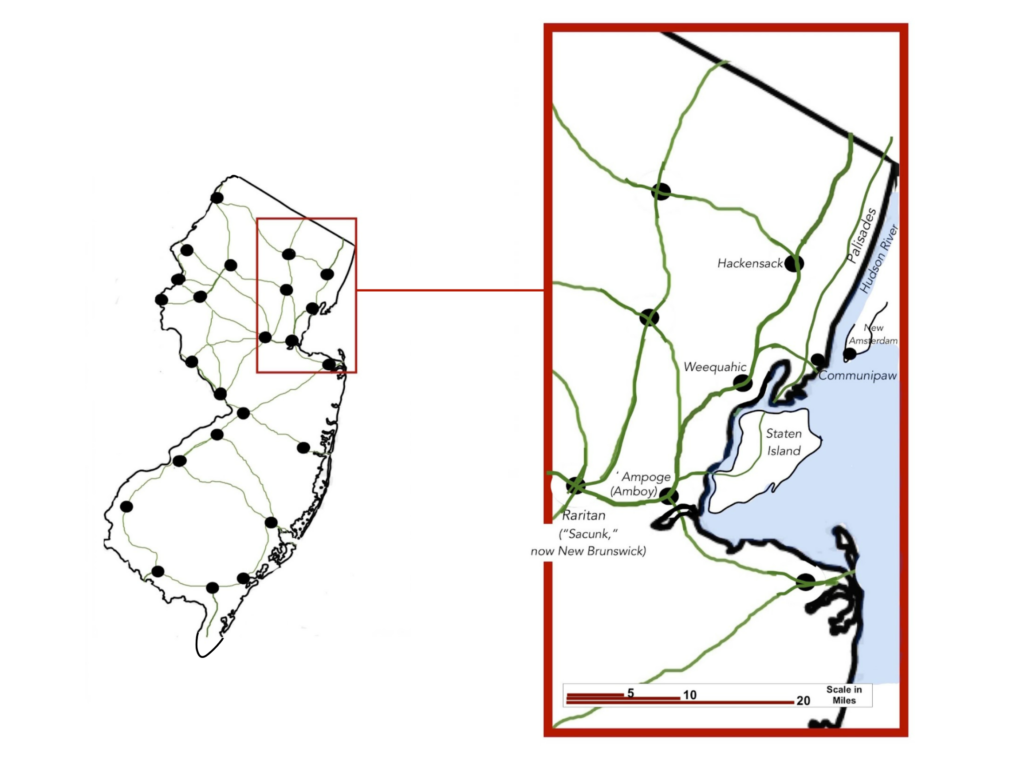

By the 1630s there were trading posts on either side of the Hudson. Landowner Michiel Pauw chose the small islands that make up “Pavonia” because he wanted to intercept the fur trade headed for Fort Amsterdam. Pauw’s land deeds from 1630 also state Indigenous place names. The deed for Ahasimus made it clear that the salt marshes surrounding these three islands were the boundaries of the land being sold to Pauw. Arresick was a small island amidst the salt marsh, strategically located directly across from Fort Amsterdam.

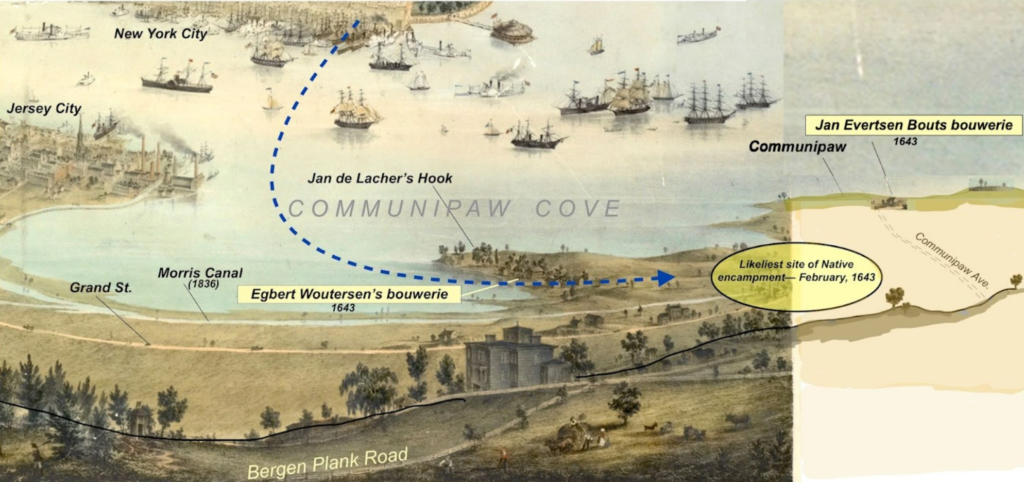

From 1634 until the massacre in 1643, the manager of the Pavonia trading station was Jan Evertsen Bout, also known as Jan de Lacher. His bouwerie was on the round knoll of upland surrounded by salt meadows, which the Dutch called Jan de Lacher’s Hoek. In addition to trading with the Lunaape/Lunaapeew/Lenape, he used enslaved African laborers (as did other Dutch planters) to grow barley, corn, and tobacco in former Indigenous managed fields at Communipaw. He leased his bouwerie to Egbert Woutersen around 1640, and moved south to a new one.

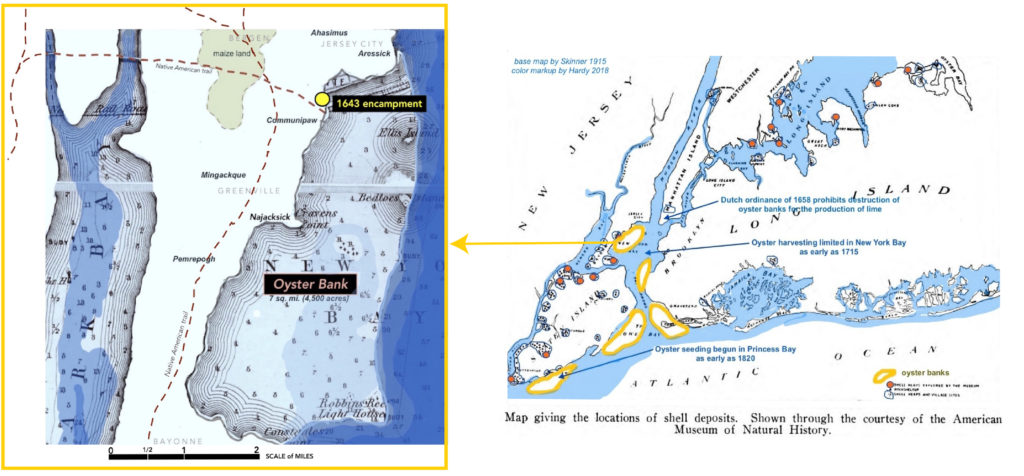

We can locate the encampment from cross-referencing various historical descriptions — “behind Egbert Woutersen’s,” “behind Jan Evertsen Bouts,” “at the oyster bank in Pavonia,”“visible from Fort Amsterdam”.

This 1854 bird’s eye view drawn from high ground in Bergen looks east across the Hudson River to New York City in the distance. Although the drawing was made in 1854, it depicts how the shoreline and landforms on the New Jersey side of the river would have largely appeared in 1643 when Hackensack and Tappan people established an emergency encampment there. The blue line shows the route taken by 80 Dutch soldiers on the night of Feb 25, 1643 to the massacre site. The area would have been more wooded in 1643 with parcels of open land such as Jan Evertsen Bout’s barley field that was 7 morgens (approximately 18 acres) in size. The shallow water of Communipaw Cove was the site of a historic oyster bank providing reliable food.The Bergen Plank Road shown in the 1854 drawing had evolved from the Indigenous footpath that once connected the Palisades to Staten Island. In all likelihood, the Hackensacks and Tappans would have come down this trail to reach Communipaw.

Pavonia Today

The place known as Pavonia is now part of the Communipaw neighborhood of Jersey City, New Jersey. Where the salt marsh led to the river itself is now cut off from the water by the New Jersey Turnpike. Just beyond this barrier is Liberty State Park, built on landfill from shipping and construction debris. Like much of the landfilled development on this side of the Hudson, the park is built on top of an historic oyster bank that was an important Indigenous food source and supported a myriad of additional multi-species relationships.

We are still here.

Not all are tucked away like parks in cities.

Closed knit, core communities and dispersed afar in cities block.

Outdated History needs correction, NY, NJ, CT, MA, RI, we are still here.

Cities subjugate nature into insignificant pockets, it is still here.

Minuscule compared to its former honor, tucked away awaiting the unexpected wanderer.

They visit, enjoy or study, unearthing teachings of heart and spirit.

Nature is still here. We are still here, with teachings of heart and spirit.

We Native Americans are synergistic, onto parks of nature.

We are not gone, we are Resilience!

We are still here.

— Michaeline Picaro Mann, Turtle Clan, Ramapough Lunaape Nation

Oyster Bank

Oysters were paramount in this estuarial region. Lunaape/Lunaapeew/Lenape people would process and dry oysters in late summer and early fall, in order to have a dependable source of winter food. Since oysters were richer in fat and higher in protein than any other wild food, easy to access and readily available in high quantities, they were the best food source in the entire region. Owing to oysters’ fecundity, and their preferred shallow-water habitat, a long list of bird, fish, and mammal species harvest them in all of their various life stages. From the earliest days of Europeans’ arrival to today’s New York and New Jersey, contemporary accounts describe large shell middens occurring all along the shore, and even at sites located well inland, marking the landscape with the significance of oysters to the region’s people.

A centuries-old footpath, preserved by today’s “Communipaw Avenue” (Rt. 9), led to seven square miles of oyster habitat off the coast of present-day Jersey City. When Verrazano anchored nearby in 1524, he noted thirty small boats of Native people fishing there. From the earliest days of Dutch exploration, the navigators’ charts routinely refer to the “Oyster Bank” or “Oyster Islands” (today’s Ellis and Liberty Islands). Despite the fact that Indigenous use of this resource was equivalent to what English law would call a “commons,” no Indigenous group ever sold the oyster bank, nor received any compensation when they were excluded from accessing it. Settlers harvested the empty shells and even dredged live oysters to make lime, and eventually created a trans-Atlantic market for the area’s oysters. Various ordinances, regulations, and laws limiting the oyster harvest, and attempting to bolster the population were implemented. Ultimately, the oyster population was destroyed by overharvesting, pollution, and finally landfilling disrupting the balance of the many relationships that it supported for millennia. It was here that, in 1643, several hundred Lunaape /Lunaapeew/Lenape peoples had established an emergency midwinter encampment with the additional help of blankets, clothing, and cornmeal supplied by friendly Dutch settlers, and bolstered by the readily available supply of oysters.

Billboard Campaign to Commemorate the 1643 Pavonia Massacre

In collaboration with For Freedoms, Josué Rivas (Mexica and Otomi) of INDÍGENA, Hôtvlkucē Harjo (Mvskôkē-Creek), The Public History Project and our Lunaape/Lunaapeew/Lenape community partners created a billboard campaign near the original site of the 1643 Pavonia Massacre. The billboard remains on view from February 24 – March 14, 2022 to resurface this under-acknowledged massacre that continues to impact our present.

Here are the accompanying social media posts on Instagram Facebook and Twitter.

The billboard is located on one of the truly ancient pathways in New Jersey which led directly to the Communipaw oyster bank. The pathway connected Weequahic (a village just south of modern Newark) on the west with Communipaw, the home of the great oyster bank, on the east. There was a major north-south trail that crossed the great ford of the Raritan and linked Weequahic, Hackensack to the Hudson River. Similarly, a north-south trail went from Staten Island up through Communipaw, then up over the Palisades. This trail became the Bergen Plank Road in colonial times. A later trail followed the shoreline north from there. In the 1600’s and 1700’s this was the route New Jersey Munsee and Unamis took to cross the Passaic and Hackensack Rivers to get their furs to New Amsterdam. These paths were called “causeways,” where cedar logs were used to help get across the wetlands. This pathway later became known as the “Newark Plank Road”; so-called because cedar logs were also laid corduroy-road fashion to enable the first carriages to cross wetland areas now known as the Meadowlands, then in turn became known as “Communipaw Avenue”.

This important path, and the Indigenous-cleared lands where it met the Hudson, were primary reasons that Michael Pauw’s agents bought this land for a patroonship in 1630. They were aware this opportunity would make theirs the first fur trade west of the Hudson. Long before Indigenous people used this path to trade beaver furs to Europeans, people used it to get oysters; and the path of today’s “U.S. Truck Route 1/9” that continues onto Communipaw Ave. carries on this function of a transportation corridor today.

Project Partners

Historical Context

Why were people camped in Pavonia and Corlears’ Hook?

The Dutch had given guns to Indigenous groups near Albany in order to control the fur trade. These groups threatened to use force to extract tribute payments from downriver tribes such as the Wickquasgecks, Tappans, and Hackensacks. Because of this, 400-500 people had fled south, setting up camp on either side of the Mahicannituck (the present-day Hudson River).

On the west side of the river, a group of several hundred people first stopped at Vriessendael, Dutch Patroon David DeVries’ farm, today known as Edgewater, NJ. DeVries had good relationships with Native peoples in the area and kept detailed journals of his time in the region. He couldn’t accommodate such a large group so they moved further south, settling near a salt marsh adjacent to the land of another trusted Dutchman, Jan Evertsen Bout, in what was then known as Pavonia. Pavonia may have been an ideal place as it was also adjacent to riverfront oyster beds which would have been a steady source of food in winter.

On February 24th, Cornelis Van Tienhoven spent the day reconnoitering the encampment. Kieft’s order, signed later that day, read:

Sergeant Rodolf is commanded and authorized to take under his command a troop of soldiers, and lead them to Pavonia, and drive away and destroy the savages being behind Jan Evertsen’s, but to spare, as much as is possible, their wives and children, and to take the savages prisoners. He may watch there for the proper opportunity to make his attack successful…The exploit to be executed at night, with the greatest caution and prudence. Our God may bless the expedition. Done, Feb 24th, 1643.

Around midnight on February 25th, a platoon of soldiers attacked the Pavonia encampment with guns and swords. A group of armed Dutch simultaneously attacked the smaller encampment at Corlears’ Hook. Around 120 Indigenous people were killed that night, including women and children. David DeVries was across the Hudson at Fort Amsterdam, in what is now lower Manhattan, and could hear the sounds that carried clearly across the water. He wrote, with horror, in his journal:

I remained that night at the governors, sitting up. I went and sat in the kitchen, when, about midnight, I heard a great shrieking, and I ran to the ramparts of the fort, and looked over to Pavonia. Saw nothing but firing, and heard the shrieks of the Indians murdered in their sleep.

DeVries later described the event in detail (most likely from the soldiers’ descriptions) and concluded that they were “…miserably massacred in a manner to move a heart of stone.”

Kieft’s brutal campaign to gain power over Indigenous peoples of the region sparked a violent response by affiliated Munsee-Mohican tribes, who felt betrayed by the Dutch with whom they had mostly lived in peace. As a chief told DeVries soon after the massacre,

[The Dutch] first came upon [our] coast; that [you] sometimes had no victuals; [we] gave [you our]… beans and…wheat, [we] helped [you] with oysters and fish to eat, and now for a reward [you] killed [our] people.

An alliance of the entire lower-Hudson Indigenous community began to attack and burn any Dutch farms and holdings outside of Fort Amsterdam, and Dutch soldiers responded in kind. What is known as “Kieft’s War” lasted more than two years; many Indigenous and colonial lives were lost, and little was gained. Kieft’s self-dealing, bad decision-making, and mismanagement of the colony led to his recall by the Dutch West India Company in 1647. While traveling back to the Netherlands, supposedly along with the large personal fortune that he had made during his time in the colony, his ship sank, and he drowned.

Further Historical Context

The English and Dutch colonial projects overlapped in time and space, and pursued similar strategies for dealing with the original inhabitants of the estuarial region. Both included some form of diplomacy and relationship-building (at least economic ones) with Indigenous communities and individuals. However, both also included kidnapping, enslavement, murder, taxation (through tributes), and interference into intertribal relations. In particular, the Dutch colonial relationship to the land and people of the region was extractive—they were there to squeeze out as much wealth and economic benefit as they could.

These colonial projects completely disrupted and changed traditional Indigenous economies, politics, and lifeways. One example is the tribute system based around wampum. Before the English and Dutch arrived, wampum was used as a medium of ceremonial and cultural exchange. Both the English and the Dutch learned quickly of wampum’s role and began to strategically accept and use it in their negotiations with Indigenous people. The Dutch monetized wampum by the 1620s and made it into a more formal currency.

These actions imposed a European capitalist structure onto the existing Indigenous cultural system of exchange. This imposed structure became a force that shaped and changed intertribal power dynamics. Wampum became one of the primary means of paying tribute between Native groups and to colonial powers, and this system was often violently enforced by both colonial and Native groups. This is why the groups were camped at Pavonia—they had been driven from their villages by groups (who had been armed by the Dutch) demanding tribute payments.

A few years before the Pavonia massacre, the English waged war against the Pequot tribe, who controlled land, fur trading, and wampum manufacturing from the Connecticut River Valley to the Narragansett territory in modern-day Rhode Island. This brutal campaign, was essentially a calculated attempt to annihilate an entire tribe. Many Pequots were killed, forced into slavery, or absorbed into other groups. Once the Pequot’s influence was gone, the English seized their lands and assumed their power in the region, including demanding tributes from coastal tribes.

The Dutch were aware of the outcomes of the military campaign against the Pequots, but lacked the strategic relationships and alliances that the English did, which were key to their success. Kieft had tried to extort tribute payments from all of the local tribes for “protection” against the upriver tribes that the Dutch themselves were selling guns to. (David DeVries was of the opinion that Kieft and Van Tienhoven hoped to personally profit from these payments, and likewise that the pair would skim–or as DeVries put it, “make a bad reckoning of”– any money sent by the Dutch West India Company to finance a war.) The lower river tribes refused to take these demands seriously. It’s likely that Kieft hoped the massacre at Pavonia would result in similar gains as the violent English campaign had against the Pequots. However, “Kieft’s War” resulted in the further destabilization of the Dutch colony, and the deaths of up to two thousand Indigenous people.

Who writes the history?

The only surviving primary written sources for the history of the Pavonia massacre are colonial. We know a lot about the perpetrators of the Pavonia massacre through these accounts, but these sources tell much less about the people who were camped at Pavonia. Much of this story is in the collective memory.

The colonial sources are a few bureaucratic accounts, land deeds, and old maps; but mainly from the journals of David DeVries. DeVries came to New Amsterdam to manage his landholdings—first, on Staten Island, and then on the west side of the Mahicannituck. He quickly learned to speak local languages, and seemed to be someone who was trusted by the Tappans, Hackensacks, Canarsees, and other local Native communities.

The massacre victims’ brief stop at DeVries’ plantation is noted in his journal. He heard from them how they had been driven south; he predicted the folly of Kieft’s impending ambush and tried to prevent it; he witnessed and heard the massacre from the ramparts of the fort.

DeVries’ journal is routinely critical of Kieft’s policies, and it also provides some of the only instances where Indigenous speakers are directly quoted, by someone who knew their language and traveled freely among them. It remains amongst the best primary source documents for understanding the early Dutch colonial era in New Netherlands.

Epilogue

The people and events that constitute history can be compared to an assortment of beads strung on a necklace — we pay perhaps too much attention to the individual beads, and not enough to the string that connects them.

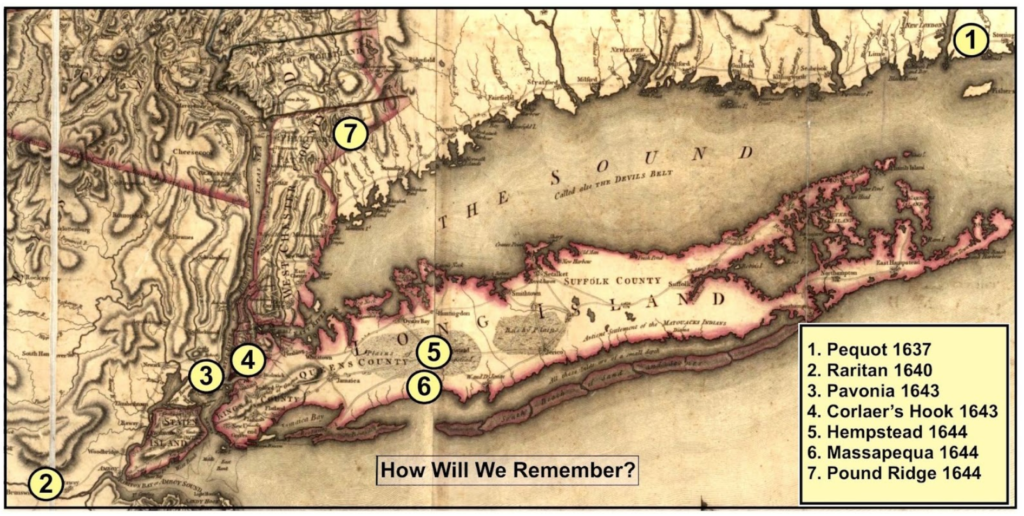

The atrocities that took place at Pavonia in 1643 are amongst at least seven other incidents in the region that can be defined as a massacre – an unnecessary, indiscriminate killing of human beings – and arguably that they are all connected by a common thread that runs from New England down through the Long Island Sound to New Amsterdam. Each of these events deserves to be separately studied and remembered, but they must also be seen collectively as part of a larger pattern.

A detailed discussion of the relationship between these seven massacre sites will be made available soon.

Resources

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- Beauchamp, W. M. (1907). Aboriginal place names of New York. Albany: New York State Education Dept.

- Bolton, Reginald Pelham. (1975). New York City in Indian possession. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation.

- Brinton, D. G. (Daniel Garrison)., Rafinesque, C. S. (Constantine Samuel). (1885). The Lenâpé and their legends: with the complete text and symbols of the Walam olum, a new translation, and an inquiry into its authenticity. Philadelphia: D.G. Brinton.

- This is a very accessible introduction to Lenape ethnology and language. It is also a good portrayal of the Lenape culture and landscape before European contact.

- Brodhead, John Romeyn, (1853 -71). History of the State of New York. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- This very comprehensive source is important for understanding how events all across the Northeast —at Boston, Albany, Connecticut, and the Delaware River— affected what happened at Pavonia. Look for names like de Vries, Pauw, Pavonia, van Twiller, Kieft, and van Thienhoven to follow the various threads of the narrative (of particular note are pages 267 through 400).

- Donck, A. V. D. & Murphy, H. C. (1854) Vertoogh van Nieu Nederland; and Breeden raedt aende Ver eenichde Nederlandsche provintien. Two rare tracts, printed in -’50. Relating to the administration of affairs in New Netherland. [New York Baker, Godwin & co., printers]

- Starting on page 140 of the Breeden Raedt (“Broad Advice”) is an account of the Pavonia Massacre. The Breeden Raedt is written in the form of a dialogue between shipmates sailing back to Europe, The character “B” is the skipper, who has first-hand knowledge of what went on in 1643 Pavonia.

- Juet, Robert. “The Third Voyage of Master Henrie Hudson” in Purchas, Samuel. Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas His Pilgrime, Contayning a History of the World in Sea Voyages and Lande Travells by Englishmen and Others. (Glasgow: James MacLehose and Sons, 1906). Volume 13, pages 333-374.

- The account of Hudson’s third voyage in 1609 details examples of some trading sessions amongst many other items of interest. It is written by Hudson’s crewmate Robert Juet.

- Nelson, W. (1894). The Indians of New Jersey: their origin and development, manners and customs, language, religion and government : with notices of some Indian place names. Paterson, N.J.: The Press Printing and Publishing Company.

- A good resource on the background of Indigenous culture of the New Jersey area. Of particular note are the discussions of place names. Also of particular note is the 260 words of trade jargon – the actual words that were used by the Dutch and the Lenape in their trading at Pavonia and Hoboken.

- Lipman, A. (2015). The Saltwater Frontier: Indians and the Contest for the American Coast. New Haven: Yale University Press

- Sanderson, E. W. (2009). Mannahatta: A natural history of New York City. New York, NY: Abrams Press

- Sanderson, E. W. The Welikia Project, The Wildlife Conservation Society, welikia.org/

- Skinner, A., Newark Museum Association. (1915). The Indians of Newark before the white men came. [Newark, N.J.]: Newark Museum Association.

- Skinner was one of the most prolific archeologists of his era in the region.

- Verrazzano, Giovanni da. The Voyage of John de Verazzano, along the Coast of North America, from Carolina to Newfoundland, A.D. 1524. (New York: New York Historical Society, 1841). Second series, volume 1, pages 37-67.

- Verrazzano’s account of his 1524 voyage commissioned by French king Francis I. He explored New York harbor and described Manhattan Island, both of which would be “forgotten” by European minds for nearly another century.

- Vries, D. Pietersz. de., Murphy, H. Cruse. (1853). Voyages from Holland to America, A.D. 1632 to 1644. New York: [Billin and Brothers, Printers].

- One of the best primary sources from the period of first contact between the Lenape and the Dutch. It also gives a very good description of the Pavonia area.

- Wissler, C. (1909). The Indians of Greater New York and the Lower Hudson. New York: The Trustees.

- A very useful reference that gives an overview of the First People of this region, and details many archaeological findings in the region.

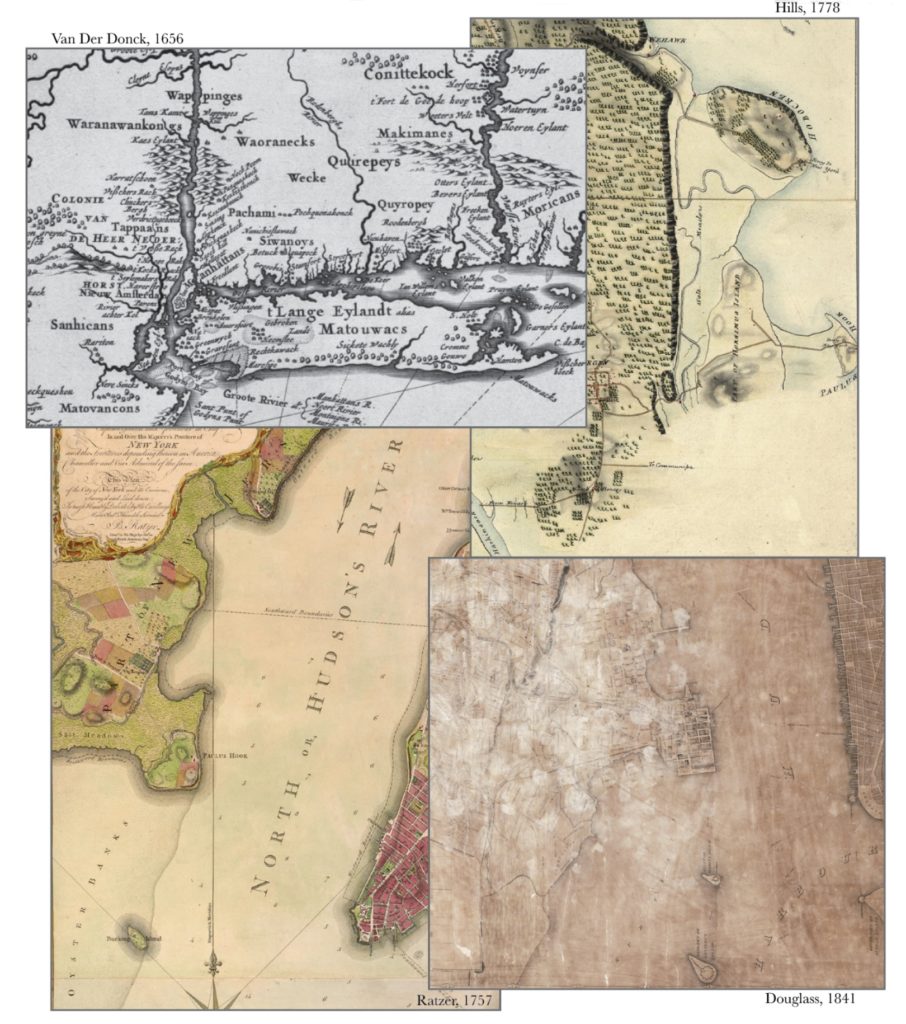

MAPS

Many of the maps referenced here can be found in the The Library of Congress (LOC) map collection.

- Bache, A. D. (1866) Map of the bays, harbors, and rivers around New York: showing the channels, sound ings, lighthouses, buoys &c., and the complete topography of the surrounding country: including Hempstead, Sandy-Hook, South-Amboy, Newark, Yonkers, N. Rochelle & Glen Cove. www.loc.gov/item/90684517/

- Douglass, L. F. & Sherman & Smith. (1841) Topographical map of Jersey City, Hoboken, and the adjacent country: describing minutely the courses of rivers and brooks, the township and original patent lines, railways, turnpike, carriage and bridle roads, the present farm boundaries with the names of their proprietors: a correct plan of public grounds and gentlemen’s country seats, the position of farm houses, forests, swamps, and marshes, showing a complete view of the face of the country. www.loc.gov/item/2009584237/

- Ratzer, B. & Kitchin, T. (1767) To His Excellency Sr. Henry Moore, Bart., captain general and governour in chief in & over the province of New York & the territories depending thereon in America, chancellor & vice admiral of the same, this plan of the city of New York is most humbly inscribed. www.loc.gov/item/91684092/

- Hills, J. & Morgan, B. (1778) Sketch of the road from Paulus Hook and Hobocken to New Bridge. www.loc.gov/ item/gm72003607/

Van Der Donck’s map of New Netherland, 1656 (Published 1845 – 1848) digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/ e99dfb50-79bb-0133-0c3b-00505686d14e