The research methodology of the Public History Project involves listening for, and retrieving, under-recognized and erased voices. This deliberately slow yet thoughtful process demands reckoning with unpleasant realities— the hidden costs of building a metropolis at the expense of a once-great estuary; the injustices of dispossessing and oppressing certain people for the wealth and advancement of others. It requires us to challenge the widely accepted, yet one-sided, colonial narrative of history, and replace it with something deeper, richer and ultimately, more reflective of the whole truth.

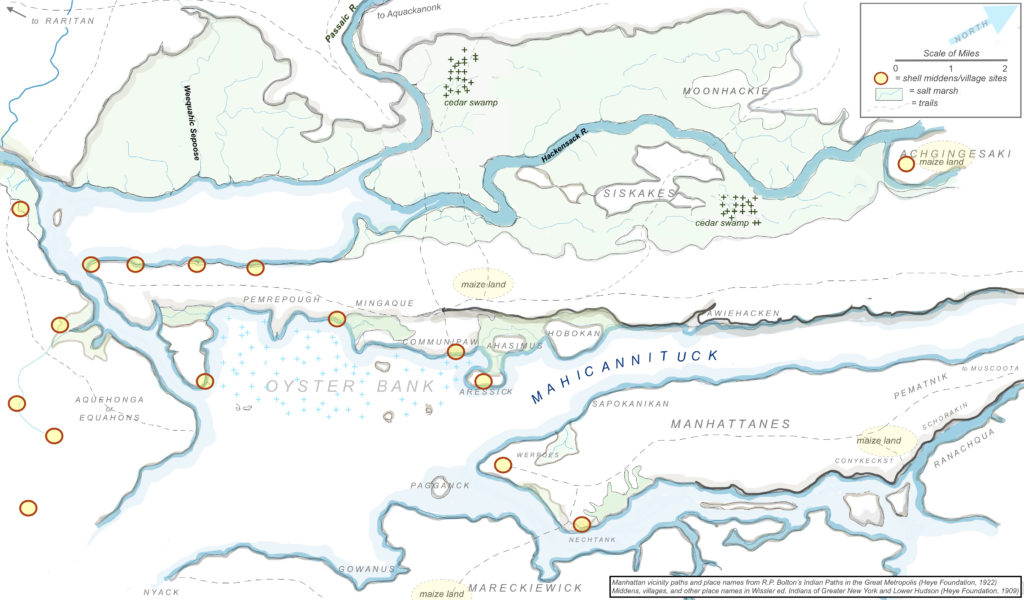

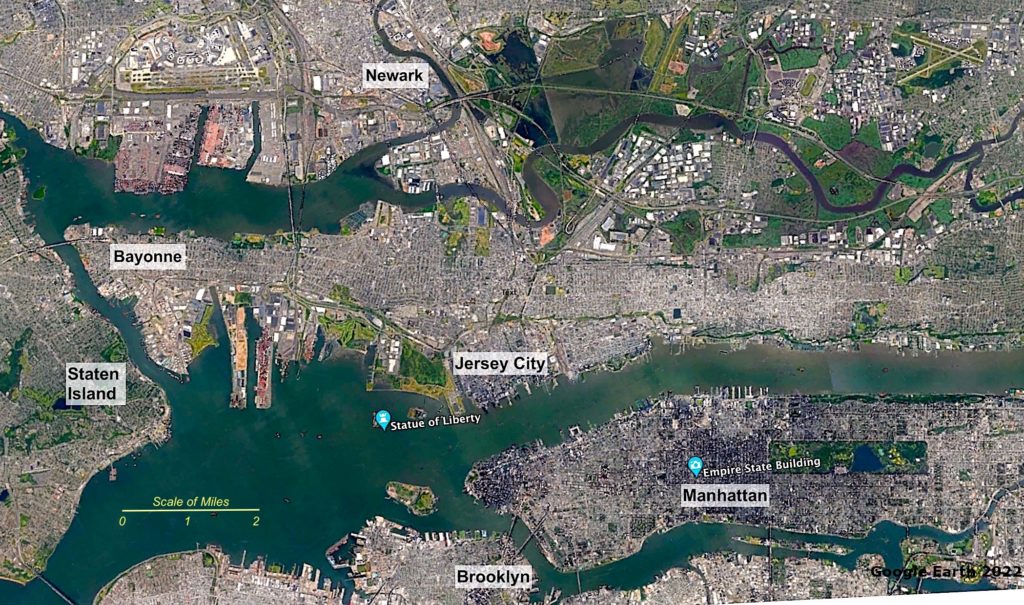

The following content are part of an unfolding series that is periodically updated to reflect PHP’s ongoing and collaborative research realized through the coming together of historians, spatial researchers, Indigenous culture bearers, ecologists and artists. Instead of being conclusive, they only begin to describe the Pre-Contact ecosystem of the lower Hudson River, or Mahicannitukw—“great tidal river”—as it is known in the original Algonquian language.

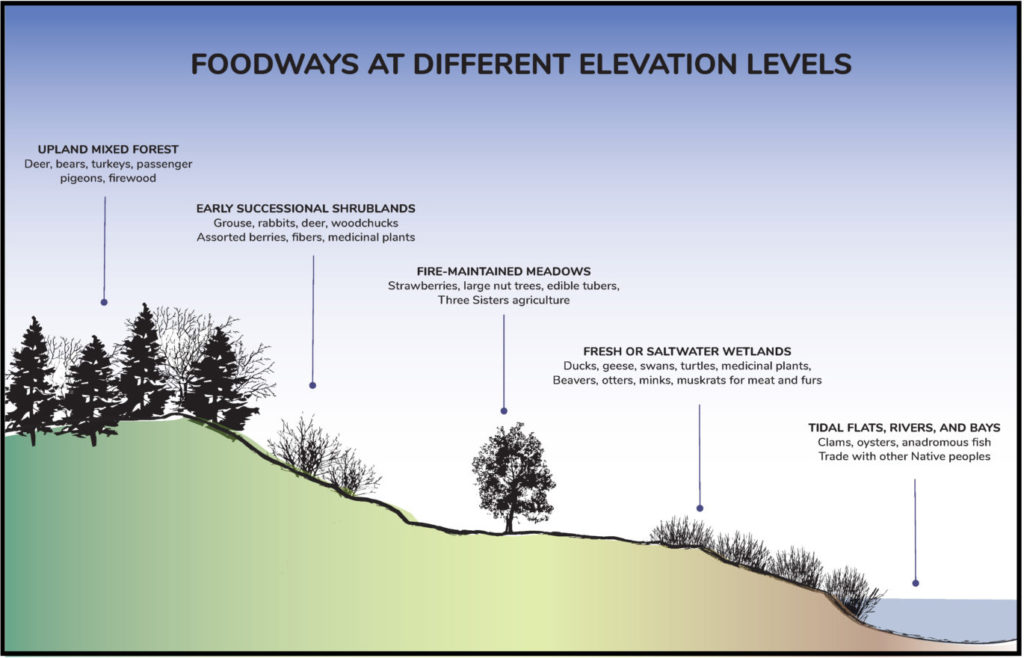

The Indigenous Foodways series reflects how Native Americans found everything they needed to survive and prosper in the bioregion—clean water, abundant food, medicinal plants, and all the other necessities of material culture. They sustainably cared for the ecosystem by only taking what they needed, gave thanks for what they took, and the vibrant ecosystem ensured plenty for all.

Indigenous place-names — be they descriptions of geographical features or indicators of prominent food sources — reveal a relational worldview the original peoples have with the land, water and non-human relations while offering insight into a pre-colonial and dynamic living world.

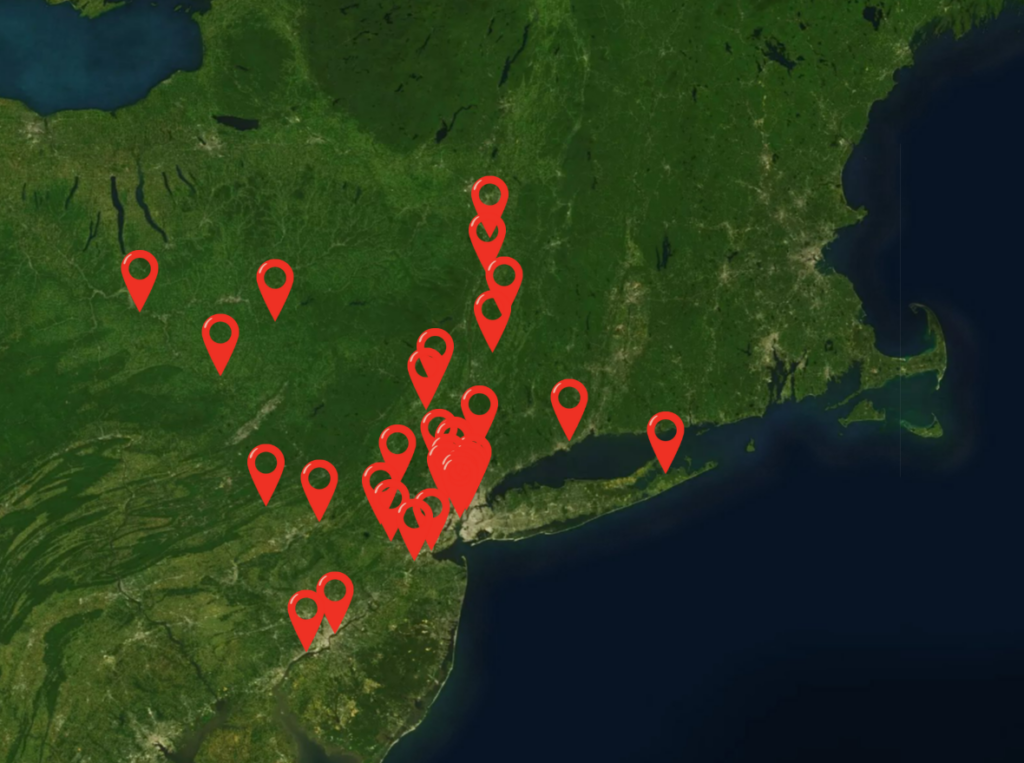

PHP is working on a forthcoming interactive Indigenous place-names map through a multidisciplinary collaboration between Algonquin linguists, ecologists, Munsee Lunaape/Lunaapeew/Lenape language teachers, spatial researchers, and artists. This is a constantly unfolding project and is by no means an exhaustive presentation of Indigenous place-names in the traditional homelands of the Lenape/Lunaape/Lunaapeew/Mahican peoples.

Do you know about one of the oldest human-made structures in the New York-Newark metropolitan area? Built by the Lunaapeew/Lunaape/Lenape people, the Passaic Fish Weir Complex was a series of at least sixteen low dams that once stretched over the lower twenty miles of the Passaic River to trap large quantities of shad fish. The weirs were in active use for millenia as well as through the early colonial time period. Many of road networks in present-day New Jersey are a result of the robust human activities surrounding the weir complex. While only one of the original sixteen weirs remains intact, these significant structures speak to the abundant Indigenous community life in the estuarial region. Follow this interactive map to learn about the archaeological, linguistic, historical and ecological significance of this site.

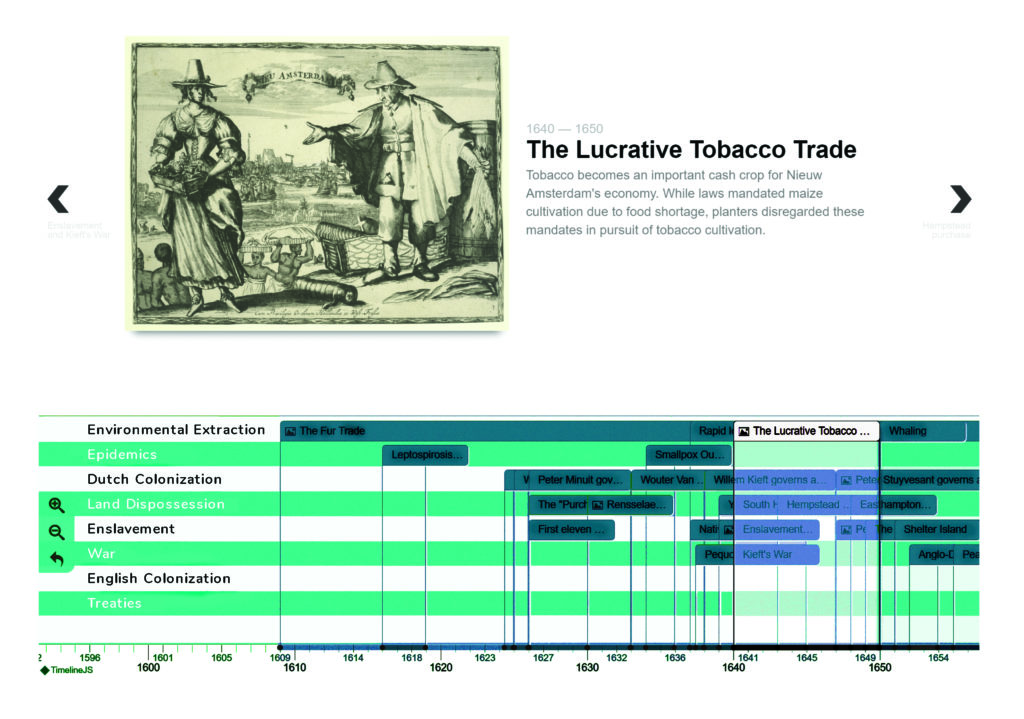

A Timeline of Dispossession, Enslavement and Extraction

Currently undergoing the process of community and interdisciplinary peer review, this interactive timeline layers the intersecting histories of dispossession, enslavement and environmental extraction in the New York-Newark estuarial region with a focus on the significant events that unfolded during 1609-1715 that left a lasting impact on the region and beyond.